by Olivia A. (’14)

I’ve played music since I took up the violin in fourth grade. Until this summer, I hadn’t deviated much from my training in classical music (“I Kissed a Girl,” “Eleanor Rigby,” and the My Little Pony theme song being notable exceptions). Over this past summer I realized that I was completely fed up with the attitude towards music of the classical musicians around me. I enjoy listening to a lot of classical music and I love a lot of the people I know who play it, so my reasoning was not so much rooted in the music itself or the people themselves. I quit viola because I personally couldn’t handle the competitive, judgmental musical culture that I was experiencing. It was difficult to quit—I have always been told to choose something and stick with it. That mentality, I’ve realized, often doesn’t suit my distracted, indecisive nature.

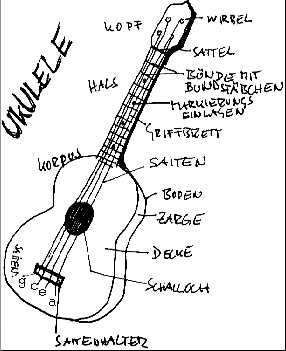

I quit my private lessons, returned my viola, and decided to try something that is nearly the polar opposite of the musical culture I had become used to—traditional Hawaiian ukulele. This style of ukulele is primarily rooted in both the meaning of the words and in the purpose of the music as a component of hula dancing. My teacher treats the lyrics as poetry, explaining how the references and symbolism in each song relate to aspects of Hawaiian culture and history. For example, in a song called “Puamana,” the English translation of a Hawaiian line is simply “the bright moon glistening.” However, one word in the Hawaiian text, “kōnane,” is actually the name of an ancient Hawaiian board game similar to checkers. White and black stones are moved around indentations in a large slab of rock, creating an effect likened to the reflection of the moon on the waves.

I quit my private lessons, returned my viola, and decided to try something that is nearly the polar opposite of the musical culture I had become used to—traditional Hawaiian ukulele. This style of ukulele is primarily rooted in both the meaning of the words and in the purpose of the music as a component of hula dancing. My teacher treats the lyrics as poetry, explaining how the references and symbolism in each song relate to aspects of Hawaiian culture and history. For example, in a song called “Puamana,” the English translation of a Hawaiian line is simply “the bright moon glistening.” However, one word in the Hawaiian text, “kōnane,” is actually the name of an ancient Hawaiian board game similar to checkers. White and black stones are moved around indentations in a large slab of rock, creating an effect likened to the reflection of the moon on the waves.

My experience learning Hawaiian music has been entirely different from my experience with classical western music. The process is much calmer, in general—I’m not constantly worrying about people judging my skill level. However, that isn’t to say that Hawaiian music is easy to play. It is difficult to strum, change chords, and sing in Hawaiian with correct pronunciation simultaneously.

I always look forward to playing the ukulele. I’ll pick it up and accidentally play for hours without realizing that I’m practicing. Similarly, I often don’t realize that in learning the music, I’m exploring Hawaiian history, culture, and poetry. It’s all begun to blend together in my mind—the way a song can reference the leaves of a tree that grows nuts whose oil can be extracted to create candles likened to a lighthouse on an island with a history about the Spanish cowboys who lent the song its Hispanic influences that influenced the culture of the island, that informs the poetry of it—I’m learning to see these islands through the songs, and I wonder how I’ve managed to learn anything in any other way.

Angst (n.): an intense feeling of apprehension, anxiety, or inner turmoil

Angst (n.): an intense feeling of apprehension, anxiety, or inner turmoil

However, if they coexist, believing in one or the other would not be wrong. Like looking at an optical illusion, seeing one thing rather than the other doesn’t make you wrong, it just limits your cognition. Sure, you can only really see one at a time, only the young lady when it’s not the old woman and vice versa, but if you can recognize that both exist then you have reached full understanding.

However, if they coexist, believing in one or the other would not be wrong. Like looking at an optical illusion, seeing one thing rather than the other doesn’t make you wrong, it just limits your cognition. Sure, you can only really see one at a time, only the young lady when it’s not the old woman and vice versa, but if you can recognize that both exist then you have reached full understanding.

Wes Anderson’s movies are charming and colorful, albeit very similar. They have funny captions, dysfunctional families, and mysterious narrators. But they all have a marvelous take-away feeling: the sensation of being warmed up inside. All his tales leave us with the need to enlighten everybody who hasn’t seen a Wes Anderson film, and Moonrise Kingdom is a good place to start, with a beautiful story about two young lovers running away on an island in Maine. This movie is very light-hearted and has a fantastic cast that include Bill Murray, Bruce Willis, Tilda Swinton, and Edward Norton, all who play their part fantastically well. The two kids, Suzy and Sam, were pen pals until they formulated a plan to escape from their respective homes and ran away into the wilderness, never to be found by their crazy parents ever again. The smile that this movie puts on your face will linger until the very end. The only problem I can see with this film is that it is a little too long. It has several perfect places to wrap things up but then continues, overstaying its welcome just a tiny bit. Also, for a pretty mellow film, the pyrotechnics start in the final act as the boy scouts are struck by lightning, the scoutmaster’s tent explodes, the Church steeple is also blown to smithereens and the movie ends in a completely ridiculous fashion. The movie unshackles itself from reality entirely but sometimes, especially in the grand finale, it feels like a little too much. This movie is extremely fun, extremely colorful, and extremely sweet. All in all, it is a fantastic film.

Wes Anderson’s movies are charming and colorful, albeit very similar. They have funny captions, dysfunctional families, and mysterious narrators. But they all have a marvelous take-away feeling: the sensation of being warmed up inside. All his tales leave us with the need to enlighten everybody who hasn’t seen a Wes Anderson film, and Moonrise Kingdom is a good place to start, with a beautiful story about two young lovers running away on an island in Maine. This movie is very light-hearted and has a fantastic cast that include Bill Murray, Bruce Willis, Tilda Swinton, and Edward Norton, all who play their part fantastically well. The two kids, Suzy and Sam, were pen pals until they formulated a plan to escape from their respective homes and ran away into the wilderness, never to be found by their crazy parents ever again. The smile that this movie puts on your face will linger until the very end. The only problem I can see with this film is that it is a little too long. It has several perfect places to wrap things up but then continues, overstaying its welcome just a tiny bit. Also, for a pretty mellow film, the pyrotechnics start in the final act as the boy scouts are struck by lightning, the scoutmaster’s tent explodes, the Church steeple is also blown to smithereens and the movie ends in a completely ridiculous fashion. The movie unshackles itself from reality entirely but sometimes, especially in the grand finale, it feels like a little too much. This movie is extremely fun, extremely colorful, and extremely sweet. All in all, it is a fantastic film.