We had only three class periods with Tongo Eisen-Martin, current poet laureate of San Francisco, yet his effect on my zest for craft was immense. He imparted countless quotable pieces of knowledge. My hand could not write them down fast enough, and more than once I had to stretch my fingers between revelations. What were perhaps most notable were his various definitions of poetry, a bottomless well of angles:

“Poetry is a play on perception.”

“Poetry is how your mind wants to communicate when not tasked with social survival.”

“Poetry is in the intersections of a place’s backstories.”

Tongo’s preface to the unit was to assure us that if the advice he gave was not proving helpful for any reason, that did not put us in the wrong, or make us worse at our craft. This introduction paved the way for a laid back environment, and set everyone in the room equal to each other in terms of whether what we had to say was valuable. This was not a throwaway sentiment either, or a false impression of understanding. I believe his words were,

“If you don’t vibe with what I say, don’t worry about it.”

“I’ll be giving you potentials, not policies.”

“The speed of light in your universe can be different than it is in mine.”

“My best line is no better than yours. It’s just that I extend them, hit them more often.”

The acknowledgement that as students we were worthy of respect, as well as not-yet-seasoned writers, was a large part of what made Tongo’s unit so beneficial to me. It did not hurt that, as many of us observed, Tongo’s intonation makes everything he says sound wise and significant.

The second day of the unit was dedicated to tips on dealing with writer’s block. I have often become frustrated in my education with the concept of manufacturing a push of creativity when writing poetry. Every one of my instructors has told me that the solution to writer’s block is to write; the act of expelling the bad poetry makes way for the good. I have ignored that lesson an egregious number of times. Writing bad lines when one could be avoiding it by not picking up the pen in the first place is horribly painful. Instead, I would wait it out, and when the next line hit me, unfortunate relief came with it. The self-righteous element of my mind said it was alright to wait for the elusive burst of inspiration, as it always yielded the best work. That is a blatant lie, but how convenient would it be if it wasn’t? I rarely pushed myself past the line where bad poetry finally turned useful again, like giving up on running water through dirty pipes until it emerges clear.

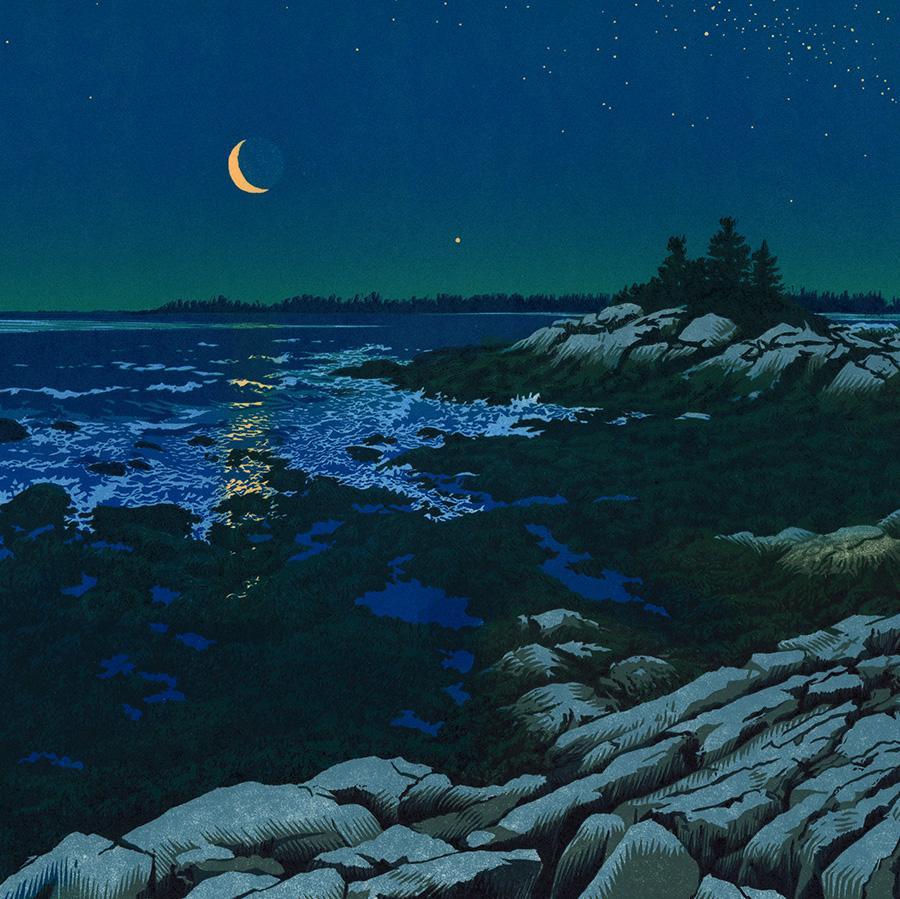

Tongo told us that “writing is the art of beating writer’s block.” From this , I was already beginning to mentally reframe the experience. He gave us a list of tricks, simple exercises and tools. For example, line one can be bad. Then make line two a negation of line one. Then make line three something both the first and second voice can agree on. I’ll give you another: think of the poem as a living picture, and work at bringing individual craft techniques to the foreground.

“Use your internal weather to induce different voices,” or

“Don’t move the camera, move yourself,” or

“In every good line, there are implied questions.”

I could go on. Would you look at that, I said to myself, writer’s block is a persistent and constant part of writing. Here are ways to play a game with it, and cheat it out of the pleasure of clogging creativity up.

Tongo’s three days with us left me with pages of nuanced perspectives and fresh tactics. And it was not only the content of his lessons but the way they were presented which struck a particularly resonant chord. Not a lecture, not a diagram of the perfect poetic process, but an honest reflection of what he had learned in his time, and what we could learn in ours.

Jessica Schott-Rosenfield, Class of ’22